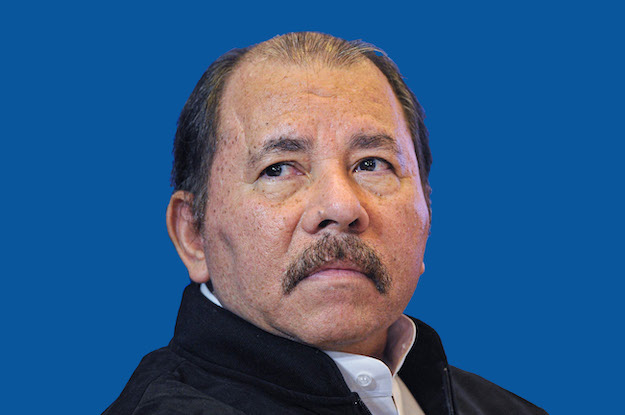

RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – If the Sandinista president were to lose next November’s elections, he would be handing over a country even more indebted than the one he handed over 1990, despite having received it 14 years ago with healthy financial statements.

When Daniel Ortega returned to power in January 2007, Nicaragua’s foreign debt reached US$3.4 billion. If the amount were distributed among the country’s inhabitants at that time, each owed about US$600. According to official data from the Central Bank, if the same distribution were made at the end of last year, each Nicaraguan would have to pay approximately US$1,900 because the foreign debt exceeded US$12 billion.

“Ortega beat his own record”, notes economist Enrique Saenz and according to this expert interviewed by Infobae, the Nicaraguan dictator would be close to setting a national historical record in terms of foreign debt.

No other president has indebted Nicaragua as much as Ortega, according to Sáenz. In 1990, when he lost the elections to Violeta Barrios de Chamorro, he handed over the country a foreign debt of approximately US$11 billion.

“The stages went like this: Violeta handed over the government with more or less six billion dollars in debt, during the government of (Arnoldo) Alemán the amount went up a little, nothing significant, practically the same debt was maintained and with (Enrique) Bolaños it was reduced to US$3.4 billion, which is what Ortega received”, explains Sáenz.

To go down from the US$11 billion of foreign debt that Daniel Ortega handed over in 1990 to the US$3.4 billion that Ortega himself received in 2007, Nicaragua underwent harsh financial adjustment programs.

“It was a sacrificial process,” Sáenz acknowledges. “The negotiations and renegotiations (of the debt) had as a condition to keep up (with payments), and to keep up in a crisis; you had to have an extremely restricted budget to be able to honor the service.”

“The process of reductions and write-offs was not for free. It ran parallel to the fulfillment of conditionalities imposed by creditors, the once-famous Paris Club, and the Monetary Fund, World Bank, and IDB. During the three governments, the impact of the economic reforms was felt by the poorest, which meant less education, health, and social spending,” he adds.

The paradoxical thing for the economist is that, even though the layoffs and budget cuts were a direct consequence of the economic crisis left by his administration, “Ortega used the reforms as a pretext to stage uprisings and protests with the organizations under his control: blockades, burning of buses and public buildings, transport stoppages and even assassinations, such as that of police chief Saúl Álvarez. And then he turned out to be the main beneficiary of the work and attrition of the governments that preceded him”.

As of December 2020, Nicaragua’s foreign debt passed US$12 billion, and with it, Daniel Ortega had returned the country to debt levels similar to those of 1990 when he left the government. “He broke his own record”, says Sáenz, and at the rate, he is going, he could set a historical record at the end of this year when according to projections, the foreign debt will reach US$13 billion, the largest debt Nicaragua will have ever had in its history.

So far, the largest debt has been carried by Violeta Chamorro’s government. “When Doña Violeta took office, the amount of the debt was close to US$11 billion, but with the inherited crisis, it reached its peak amount of US$12.5 billion by inertia. We have not yet reached that amount, but we will certainly reach it by the end of this year due to the contracts that have been signed”, Sáenz points out.

Nicaragua’s current foreign debt is similar to its Gross Domestic Product (GDP). “A 100 percent ratio between foreign debt and GDP is an aggravating indicator,” warns Saenz.

“Logically, if the debt grows, payments grow. In 2017, debt service amounted to $225 million. And in 2021, US$353 million were paid. In other words, the economy fell, but the State’s payments to external creditors increased by US125 million. And for the next few years, this amount will continue to increase”, he adds.

The foreign debt is divided into “public foreign debt”, which amounts to seven billion dollars, and “private foreign debt” comprises the remaining five billion dollars.

However, it is striking for the economist that the “private debt” comes mainly from Venezuelan oil cooperation, administered “privately” by the same group that governs together with Ortega.

For Sáenz, the first thing a new government should do is to make the debt with Venezuela transparent and dissociate itself from the commitments assumed privately by the group close to Ortega, because he fears that arrangements are being made “under the table” to convert the “private foreign debt” into “public foreign debt”.

The next step for Ortega’s possible successors will be to consider renegotiations, as did the governments that succeeded him in 1990, because “the higher the service, the tighter the budget’s neck is squeezed”.

If Ortega were to lose next November’s elections, in January 2022, he would be handing over a country as much or even more indebted than the one he handed over to Violeta Barrios de Chamorro in 1990, despite having received it 14 years ago with healthy financial statements.

“In political terms, Daniel Ortega wasted the opportunity to consolidate a shift towards a republican, democratic state, but also in economic terms, he wasted the opportunity because he received the country in the best conditions compared to any previous government”, says Saenz.

Enrique Bolaños, Ortega’s predecessor president, famously used the phrase “la mesa servida” (the served table) to describe the economic situation he inherited from Ortega.

“Ortega had not only a decreased debt service but also some US$500 million per year in available credits, the inaugural stage of Cafta (free trade agreement with Central America, the Dominican Republic, and the United States), more or less balanced fiscal accounts, economic growth, inflation under control and a positive expectation from economic agents (businessmen),” he explains.

“It had between 500 and 550 million dollars annually, additional, absolutely concessional from Venezuelan oil cooperation,” he adds. “It was as if we were producing oil, without producing it!”

“We had the opportunity to leap the strategic aspects of the country: education, professional technical training, university education, infrastructure, productivity, and all that opportunity was squandered. We still have six years of average schooling, very high levels of unemployment, and underemployment. Investment is promoted in Nicaragua because it pays the lowest minimum wage in Central America. It is a failed economic and social model,” laments the economist.

Source: infobae