RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – Latin American countries have flirted with economic liberalism in recent decades. Much of the time the liberal pledges have remained only in discourse or have been tested erratically in reality. But a small country of 17 million people may be the new laboratory for these ideas in Latin America, soon to be led by a root liberal.

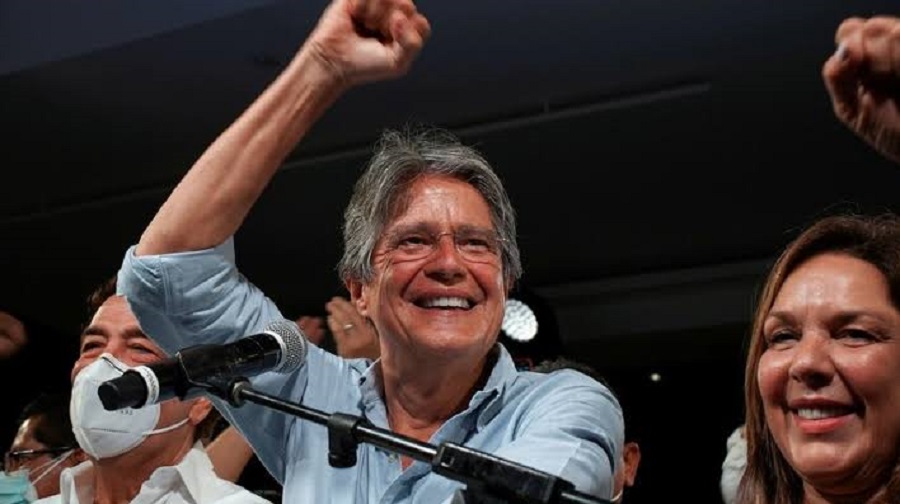

At his inauguration on May 24th, Ecuador’s new president-elect, former banker and businessman Guillermo Lasso, will be handed a country with a “completely broken social fabric.” And he will need to prove that a shock of liberalism (and good public policy) is capable of changing this.

The analysis is from political scientist and jurist Pedro Donoso, general director of the consulting firm Icare Inteligencia Comunicacional. Based in Quito, Donoso follows the political process in the country in depth, and his thesis is that the liberal proposals sold during the campaign will, from now on, be molded to a reality that is less favorable.

Lasso is the first president elected without support from Correism in 14 years, since Rafael Correa (2007-2017) first came to power. But the tight score of Sunday’s election, April 11th, with 53% of the vote for Lasso against leftist economist Andrés Arauz – added to the high number of null votes – show how the president-elect did not win unanimously, and only capitalized on part of the rejection of his opponent.

This is the immediate problem that other economically liberal Latin American politicians have had to deal with: the rejection of the previous government does not necessarily translate into support for the new mandate.

Between opposition to Correism and concrete support for the president-elect, there is a chasm. Lasso will have little base in Congress and will need to agglutinate the diverse groups that supported him. “The spectrum that he represents, an anti-correist spectrum, is very broad. That creates a lot of expectation, and the main enemy of politicians is always expectation,” Donoso says.

On the campaign trail, the president-elect said he wants to open up the economy, reduce the size of the state, make bilateral agreements, attract investors, reduce taxes, invest in agribusiness and create 2 million jobs.

But his record is not promising. With high inequality (and growing pandemic), Latin America has trouble finding ideal models of liberal government. Leaders, even those on the right, usually end up employing extensive public spending – some justified, others not so much. The reforms promised during campaigns often fail to materialize or go terribly wrong.

There are several recent examples: from Mauricio Macri’s Argentina, which did not manage to get the economy back on track after Kirchnerism, to Bolsonaro and Paulo Guedes’ Brazil, where reforms have not yet taken off. Even Chile, the flag of neoliberalism’s success and whose population has started to question the minimal state model in the last years, was included in the list.

Within Ecuador, the current president, Lenín Moreno (who beat Lasso himself in 2017), broke with Rafael Correa halfway through his term and saw his popularity plummet after subsidy cuts that led to a wave of indigenous protests in October 2019. The measures were a counterpart to a loan with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), criticized by the opposition. The pandemic has finished devastating the government, which ends its term with popularity in the neighborhood of 10%.

At 65, Lasso was president of Ecuador’s Guayaquil Bank for almost 20 years and has also worked for Coca-Cola and other private sector organizations. But he has never held elective office, having lost presidential elections in 2013 and 2017. Before that, he served for only a few months in the government of former President Jamil Muhuad, back in the 1990s.

The new president takes over a country with a devastated economy, with unemployment at more than 30% (not counting informal workers without wages in the pandemic) and an 8 percent drop in gross domestic product by 2020. At the beginning of the pandemic, Ecuador saw its health and funeral systems collapse, even having bodies in the streets. Now, the second wave ravaging South America is a new concern.

The vaccine has reached less than 3% of the population. In a promise “à la Biden” – who said he would apply 100 million doses of vaccine within 100 days in office, and then doubled the goal – Lasso promised to vaccinate 9 million people in his first 100 days.

The many congratulations the president-elect has received from right-wing leaders in Latin America show that all eyes will be on Ecuador. If successful in the country’s complicated landscape, the former banker could lay the groundwork for other liberal governments in the region that are now widely questioned. “Lasso should try to make strong shock policies, make decisions, taking advantage that he is a new president. And that may generate some kind of positivity for him,” Donoso says. “But it will be a challenge.”

Source: Exame