By Fabián Medina Sánchez

RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – (Infobae) The population calls them “Black Sundays”. Every Sunday fuel stations in Nicaragua change the prices of their displays. In the past they used to go up or down, according to the behavior of the international hydrocarbons market.

But since 19 weeks ago, fuel prices stopped going down and have only gone up, to become the most expensive in Central America.

None of the commercial reasons given explain these prices, says economist Enrique Saénz who wonders: “How is it that the rest of the countries in the region, which do not produce oil and with conditions similar to ours, have prices 50 cents on average per gallon lower than Nicaragua’s?”

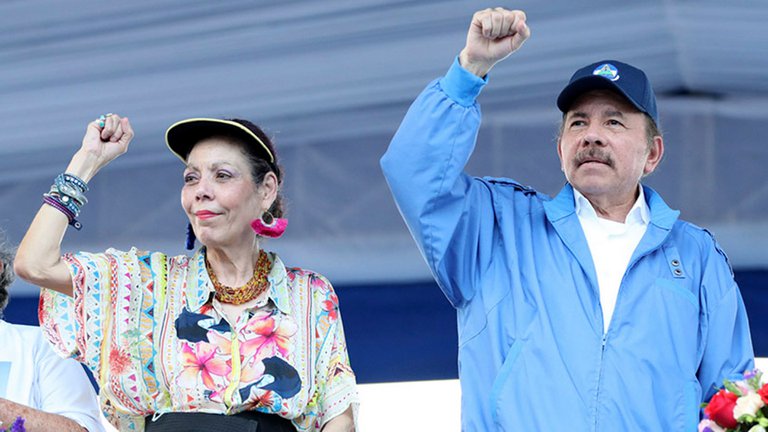

“There is a monopoly in the importation and distribution of fuel and that monopoly is held by the Ortega Murillo family,” assures also economist Oscar Rene Vargas. “They determine the prices as they wish and that money does not go to the State but to the private property of the Ortega and Murillo family.”

Enrique Sáenz thinks the same. According to the economist, in order to demonstrate the overpricing of fuels in Nicaragua, it is necessary to analyze the profit margins of the business in comparison with other countries in the area and not always the final price, because the taxes charged are different in each country.

Read: Venezuela and Nicaragua on fast track to dictatorship, says Freedom House

A study by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) found that Nicaragua’s profit margins began to diverge sharply from the profit margins of other Central American countries in 2007.

“What happened after 2007?” asks Enrique Saenz. “Two things: in the first place, Daniel Ortega came to power and, secondly, they took over the monopoly of imports and part of the distribution of hydrocarbons.”

Sáenz insists that the explanation for the current prices can be found in the past. He recalls that in the government prior to Ortega, with the presidency of Enrique Bolaños, the hydrocarbons business in Nicaragua was also in private hands and the profit margins were more or less the same as in other Central American countries.

After Ortega came to power in January 2007, an agreement with Venezuela was established and Albanisa was created, a powerful bi-national company that would handle almost all imports of oil and finished fuels, some six million barrels per year.

According to Albanisa’s articles of incorporation, 49 percent of the shares belonged to state-owned Petróleos de Nicaragua (Petronic) and the remaining 51 percent to Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA). However, it was soon questioned that the Nicaraguan state participation basically served to make state resources available to Albanisa, and the secrecy with which the accounts were handled made it impossible to see who kept the profits.

By 2011, Petronic reported profits to the national budget in the order of only two million dollars, when the company was already managing operations in excess of 400 million dollars a year.

In order to store Venezuelan oil and fuel, Ortega stripped the Esso company of the storage tanks it leased, under the argument that they would be managed by the State. In order to remove the U.S. oil company from the market, it was alleged that it had been charged 5.5 million dollars in unpaid taxes in previous years.

The secrecy with which information is handled in Nicaragua prevents establishing with documents who keeps the profits and who are the owners of the companies created under the shadow of Albanisa. The Public Registry of Property became “clandestine”, in such a way that a citizen cannot know without authorization of the company who are the partners and the capital they manage or simply find the creation of a new company. However, there are many threads that lead to the Ortega Murillo family.

Read: Journalists condemn attacks on freedom of expression and information in Nicaragua

The company Distribuidora Nicaragüense de Petróleo (DNP) acquired in 2009 by Albanisa to distribute fuel in the country, was managed by Yadira Leets until 2018, the then wife of Rafael Ortega Murillo, son of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo.

In December 2019, Nicaraguans learned of the existence of a company called Zanzibar S. A. which was sanctioned by the US Treasury Department allegedly for hiding the profits of DNP, which was also sanctioned on that occasion. The Zanzibar company was managed by Rafael Ortega Murillo and the offices were inside the housing complex that the Ortega Murillo family has established to live and manage the country. This complex has a security perimeter that prevents public access.

“There is a monopoly that they clearly established from oil imports from Venezuela. This control lasted for several years until Venezuelan oil cooperation collapsed. The oil distribution company (DNP) magically, because no one knew the explanation, became the private property of the family in government. For a long time they not only had a monopoly on imports, but also a near monopoly on storage and a slice of distribution,” explains Sáenz.

“With the DNP sanctions they invented some companies to try to cushion the blow,” he adds. “Evidently there is no evidence to prove that they are the ones who are taking this overpricing in the bag, however, it is natural to assume a conspiracy and I can, at my own risk, issue this opinion, there being no other explanation.”

In order to justify the fuel prices in Nicaragua, it has been alleged by the government and the parties involved that Nicaragua has no port in the Caribbean and therefore the fuel coming from the Gulf of Mexico must go around the Panama Canal to be able to unload in the Nicaraguan Pacific. It has also been said that Nicaragua’s reduced storage capacity prevents it from buying more oil when its price is down.

Read: Nicaragua’s Parliament Passes Law to Sideline Adversaries in 2021 Election

“It is not because of oil prices or because Nicaragua has no port in the Caribbean, because in the same situation are El Salvador and Guatemala whose prices are lower,” says the economist. Regarding storage, he recommends that a country’s capacity should be measured by time and not by volume. “How many months of consumption does a country have the capacity to store? There we see that Nicaragua is not the lowest in Central America,” he says.

Engineer César Arévalo, an expert in hydrocarbons, goes further: he assures that there is collusion with the regional oil companies operating in Nicaragua, who, since Albanisa was put out of business by the US sanctions, are in charge of oil imports. “Why in El Salvador does the same company UNO or PUMA sell a gallon of fuel cheaper than in one of their stations in Nicaragua?” he asks.

A Nicaraguan pays about 70 cents more for a gallon of super gasoline and 82 cents more per gallon of regular gasoline than a Salvadoran pays in his country.

Arevalo considers that those who manage the hydrocarbon business in Nicaragua increased their profit margins during the years of low oil prices. They did not lower prices in the same proportion as oil prices fell, and they got used to those margins, he says.

Enrique Sáenz considers that the upward scale suffered by fuels in the country is determined by the blow of the sanctions to what he calls “mafia in power”.

“The sanctions and the financial siege on the mafia in power are causing strong economic damage. As the international financial siege is tightening for these shady businesses, they have to find a way to compensate for those losses and they are doing it in a way that is not only irresponsible, but almost criminal, by unloading the machete on the backs of Nicaraguans”, he affirms.

Read: United States Imposes Further Sanctions on Nicaragua and Cuba

“They are playing with fire,” he asserts. “They are miscalculating the patience of the Nicaraguan people, they are miscalculating the repressive capacity they have, and the intimidating capacity they have because this not only affects the motorcyclist or the cab driver, but it affects the producers. Every Nicaraguan is being robbed of everything he consumes.”

According to Saénz, the oil surcharge punishes an impoverished population. “According to official figures, almost 70 percent of the population is underemployed, that is, they work every other day, or earn less than the minimum wage or are openly unemployed”.

Oscar Rene Vargas, economist and sociologist, considers that the money from the fuel surcharge is destined to cover the expenses of the regime which were previously paid with Venezuelan cooperation, among them the paramilitary payroll, which according to his calculations is between five thousand and ten thousand elements.

“Through this oil surcharge they make Nicaraguans pay their own repressors, the paramilitaries,” he concludes.