RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – Despite the pandemic, most of the region’s large criminal organizations survived by rapidly and efficiently adjusting to the new circumstances, even more so than governments, and in 2021 should continue to implement the strategies learned during the pandemic for economic rebound

Experts point out that the adjustment of the main criminal organizations was swift and efficient, opening new markets and succeeding in sustaining themselves despite the economic shock.

The coronavirus pandemic caused economic stagnation worldwide, and the criminal world was no exception. Restrictions on mobility, transnational trade, border and airport closures, and other measures implemented during quarantines hindered criminal activities and forced large organizations that own Latin America’s illegal economy to adjust to the so-called “new reality”.

This led to a considerable decrease in the different types of illegal trafficking in the region, such as cocaine (and other hard drugs), wood, gold, human and wildlife trafficking.

Given this scenario, the question is if these changes respond only to the current situation or if the dynamics of crime in Latin America have structurally changed.

Experts in safety and crime were consulted on the diagnostics and projections for organized crime in 2021 and this is what they said.

Consensus on the impact but not on the explanations

“In quantitative terms there is consensus on some assessments but not on their reasons,” says Frédéric Massé, Co-Director of the CORAL Network (Network for Monitoring Organized Crime in Latin America).

According to Massé, the different types of trafficking last year sustained an estimated 30% to 40% drop in activity compared to pre-pandemic years, a blow that is undoubtedly severe yet not enough to bring them to an end.

“Business continued,” says the expert, pointing out that “the decline was most felt when there was strict quarantine in countries where trafficking occurs.”

He mentions the case of Peru, where there was a decrease in cocaine trafficking, but in Colombia this same phenomenon did not occur. “There is no consensus because it depends on the products, data and countries,” he explains.

Among the explanations given by the experts for this decrease in trafficking are supply problems, logistical challenges, or demand in consumer countries.

Each of these points have specific features, depending on the sub-region, the product or the organized criminal groups analyzed. In the case of gold or timber trafficking, for instance, supply was not a problem, but while gold income remained virtually the same as in pre-pandemic times, in the case of timber, logging did not decrease but trafficking did.

The logistical aspect is an explanation shared by Massé and Professor Luis Fernando Trejos, doctor in Latin American Studies and an expert in conflict.

“The total shutdown of airports and land trade within Latin American countries impacted the shipment of cocaine and other illegal goods,” says Trejos.

“By reducing international trade, the pandemic reduced the chances of logistical transport,” complements Massé.

Both emphasize that the traditional means of transnational trafficking, which is supported by legal trade, such as drug mules, infiltration of containers in ships or in cargo flights, etc., were heavily affected by quarantine measures. They also claim that illegal means of transport, such as speedboats, light aircraft, or other clandestine methods, were more exposed to the decline in formal trade, making them easier to detect.

But Massé cautions, “it is also possible that criminal organizations kept their goods waiting for better times,” noting that the figures available at this time are not entirely accurate.

All of this also led to a decrease in the demand for products, particularly in the drug market, since confinement made it difficult for consumers to source their supplies.

For Andrei Serbin Pont, director of CRIES (Regional Coordinator of Economic and Social Research) and expert in safety and conflicts, although at the start of the pandemic – particularly in countries with strict quarantines – some illegal activities were paralyzed due to the increased police presence in urban centers, “they eventually resumed their course,” something that proves the shortcomings of police efforts in fighting illegal activities.

As a result, criminal structures were able to adjust, which according to experts was done faster and more effectively than the governments themselves.

New methods, niches and routes

According to InSight Crime’s projections for 2021, cybercrime was a practice that gained traction last year and seems to be a new source of income for criminal organizations this year.

“It’s not the usual phishing scams and credit and debit card cloning during online consumer transactions, but rather the whole process of transferring money, setting up businesses, creating and managing mortgages, and many other ways of doing business online,” they say.

Serbin Pont agrees, and says that in countries where subsidies were implemented for the most vulnerable populations this became a new niche for scams, extortion and other criminal activities.

The use of bitcoin and other types of crypto-currency to pay for criminal services is yet another booming practice, although Massé argues that this was happening long before the pandemic. “The use of the Darknet has been going on for many years, as has the whole laundering through cryptocurrencies. Criminals have not waited for the pandemic to go online, they were much more prepared because they have been trafficking on the Internet for years.”

Another ‘adjustment’ that InSight Crime highlights is the increase in the use of narco-submarines over the last few years as a transoceanic cargo transport system.

According to figures compiled by the organization, which mentions among its sources the investigations of H.I. Sutton, a specialist in monitoring and analyzing narco-submarines, the surge in the use of this type of transport occurred in 2018, when 35 cases were recorded, more than double the 16 the year before. In 2019, a historic record was registered with 39 cases, and although the 30 cases reported up to November 2020 indicated a slight decline, everything suggests that this is a means of illegal transport that will be used more and more.

Countries like Colombia, particularly in its Pacific region, have specialized in the building of these artisanal vessels capable of carrying up to 3,000 kilos of cocaine, like the one that sank off the Spanish coast of Galicia in late 2019.

These narco-submarines typically sail from Colombia and use the beaches of Margarita Island as a refueling and cargo hub, from where they continue their journey either towards Central America, with Mexico as their main destination, or to Europe.

“There was a higher percentage of seizures of submersible submarines made in the Pacific. That would imply that criminal organizations are looking for their own and exclusive means of transportation,” says Trejos.

The expert also points out that Central America has once again become one of the most used routes for the transit of cocaine on the continent, something that had not happened in over a decade.

The use of small planes flying from Venezuela to Honduras and from there to Mexico resurfaced last year on the “Central American cocaine highway”, which is fed by the permissiveness or complicity of the police authorities in these countries.

The figures show that during the first seven months of 2020, more cocaine was seized in Honduras than in all of 2019. By September, security forces had destroyed over 30 airstrips concealed in the jungles of the country’s northeast.

But also Guatemala – where remote airstrips for jet planes capable of carrying up to five tons of cocaine were reportedly burned – and Costa Rica – where 37 tons of cocaine, more than half of all the previous year’s seizures, were confiscated through October – have come back to the region’s drug trafficking map.

Moreover, countries such as El Salvador and Nicaragua are entering the game as their land routes are reactivated in a domino effect to move the product throughout Central America.

The border issue

This is an old issue; borders are often fertile ground for crime, particularly in countries where illegal armed groups operate through territorial control.

In this respect, Serbin Pont points out that special focus in 2021 is on the unfolding of the complex situation of the triple border between Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay. According to the director of CRIES, there has been considerable growth of the PCC (Primeiro Comando da Capital) and some other organized Brazilian factions on the Paraguayan side of the border for the past two years.

The PCC is a crime society that was founded in Brazilian jails, starting in São Paulo almost 20 years ago and from there it has spread to virtually all Brazilian states, even achieving international reach. In Paraguay the EPP (Ejército del Pueblo Paraguayo) operates, a small guerrilla organization with a Marxist orientation which has become a link to the Brazilian narcotics in the country.

“There is a greater presence of these groups in northern Argentina. They are using Argentina as a refuge or buffer zone, particularly when they have arrest warrants on them. But they will probably continue to grow in the south as they look for alternative ports to ship their products to Europe and other parts of the world,” says Serbin Pont.

A separate case is the border between Colombia and Venezuela, where a diverse cocktail of illegal armed groups coexists. The ELN, different dissident groups from the former FARC, others with a paramilitary orientation such as the Gulf Clan, or the Rastrojos, and a variety of Chavista collectives are all present there.

“Since the political and social deterioration of the Venezuelan regime began in 2015, criminal activity on the border has escalated,” says Trejos.

This is due to several factors: a historical presence of illegal Colombian armed actors – such as the abovementioned – and the fact that the Maduro regime has increasingly expanded its alliances with them. “In practice, this means that in some states the Venezuelan regime has delegated control of the border to Colombian groups,” he notes.

As in the case of Argentina with the PCC and the EPP, Venezuela is a strategic rearguard for the Colombian guerrillas. In addition to the documented presence of Jesús Santrich and Iván Márquez, leaders of the “Nueva Marquetalia” in the neighboring country, Trejos points out that the main Colombian armed player in Venezuela is the ELN guerrillas.

For Professor Luis Fernando Trejos, the ELN could be considered a binational guerrilla group today, since it has a presence, territorial control and illegal profits in both Colombia and Venezuela. “Today the ELN is a binational guerrilla, it is now a Colombian-Venezuelan guerrilla,” says Trejos.

The political-military organization collects profits on both sides of the border and exercises territorial control over Colombian and Venezuelan populations. “This border is known as a lawless area, neither the Colombian nor Venezuelan state exercises full sovereignty over this territory, it is shared by criminal organizations,” he stresses.

Degradation of crime

For Frédéric Massé, most of these structural changes were occurring before the pandemic, so the specific dynamics produced by the pandemic are more likely to be circumstantial, a kind of “pause” in the activities of organized crime that will go back to normal once life does.

This perception leads drug cartels, armed groups and large Latin American mafias to beg, as we all do, for a prompt vaccination that will soon make strict quarantines a thing of the past.

However, the expert emphasizes that large criminal organizations will not be the most affected if this does not happen, because they are prepared to survive a new confinement.

“We could talk about a pause, but the pandemic will not necessarily produce a disruption in Latin American trafficking,” he says.

Trejos agrees but adds that this survival could produce a “criminal Darwinism” in which larger organizations will “depredate” the smaller ones and assume their roles in the criminal network within their countries.

This is a “degradation of criminality” because income that is not being obtained from transnational trafficking will increasingly be sought within the populations and territories where these organizations exercise control or have a large presence.

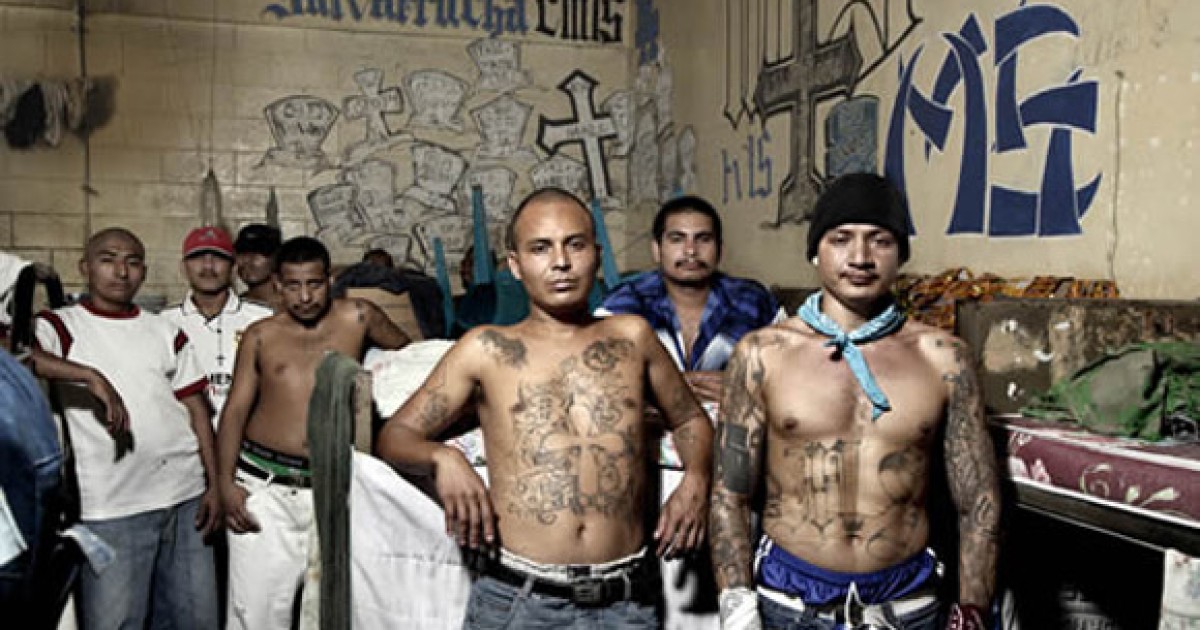

During the pandemic, criminal groups in Mexico, Brazil, El Salvador, Honduras, Venezuela and Colombia took advantage of the situation to reinforce their social control over the population, taking it upon themselves to enforce quarantine measures, create their own curfews and, in some locations, distribute food and medicine to enhance their legitimacy.

These rules, often imposed through blood and gunfire, partly explain the soaring numbers of massacres in countries such as Colombia, which closed 2020 with 381 people killed in 91 massacres, according to the Indepaz NGO.

For Trejos, the outlook for 2021 is not very encouraging: smuggling of medicines and health products, raids of stores and homes, increased extortion in the few stores that remain in operation during the second confinement and eventually a resurgence in kidnappings.

Massé stresses the diversification of trafficked products, such as anti Covid-19 drugs and some vaccines, as well as legal medicines, are part of the traffickers’ new portfolio. “There will be no structural changes,” he points out.

“In 2021 we are going to feel the real economic impact caused by the pandemic and this will lead to social degradation,” concludes Trejos.

Source: infobae