RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – (Opinion) In the 6th century, the plague struck in Constantinople. Emperor Justinian, the ruler of the Eastern Roman Empire, well on his way to reconquer Western Rome from the barbarians, became infected. He survived the disease but his armies fell apart. The conquered territories rebelled, and the plan failed.

When the plague finally passed mid-eighth century, the world was a different place. The new religion of Islam ruled in parts of the former empire, and in Western Europe, the Franks spread.

“Plagues and Peoples” is the title of a book by the American historian William McNeill. But people, not microbes, make history. The way societies react to mass contagions through time differs.

Sometimes the epidemic acts as an equalizer and reduces the gap between the wealthy and the poor; sometimes it exacerbates inequality. When plagues in the late Middle Ages drastically reduced the number of workers and made farmers a scarce commodity for landowners, the balance of power between the classes changed.

In England, the peasants rebelled and demanded to be able to freely negotiate their labor contracts with the nobles. The uprising was crushed, but the feudal order wavered, and soon landowners and urban employers began to compete for the scarce labor force.

In Eastern Europe (from Prussia to Russia), the same epidemic-driven shortage led to the nobility enslaving the surviving workers. With long-term consequences, as historian Walter Scheidel writes: Over time, the solution to the corporative grip of the West led to better wages, increased labor productivity, and economic growth. The east of the continent was left behind in this modernization process for a long time.

The interpretation of the crisis

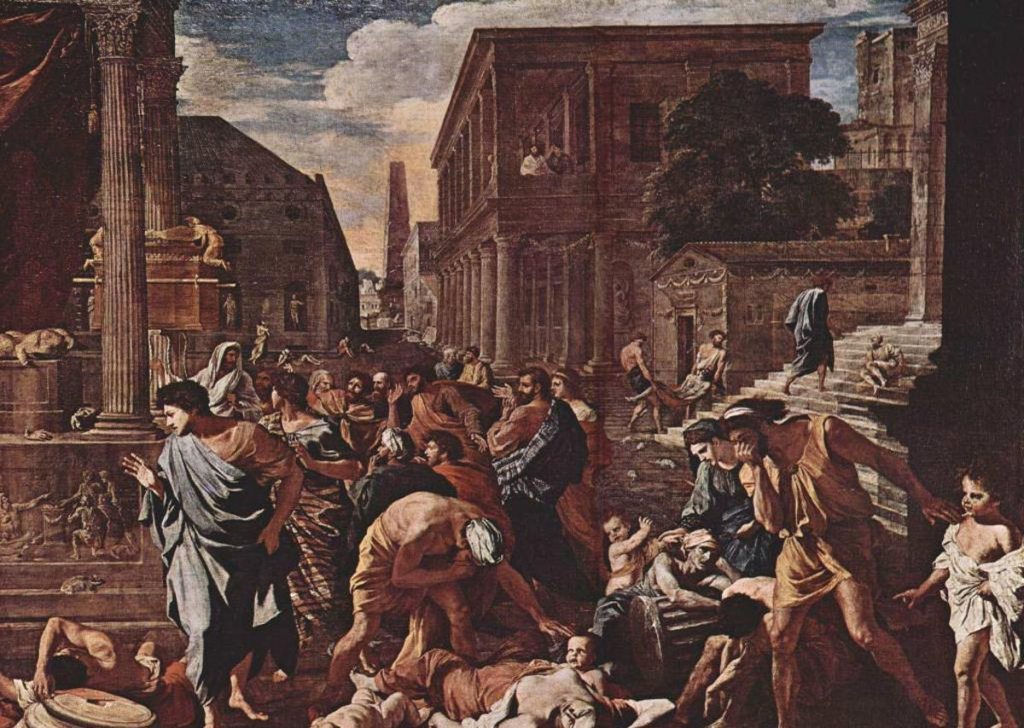

Diseases are social catastrophes that must be interpreted by those affected. They require a sense of meaning – and this sense is time-dependent. What does a person in the Middle Ages think when cemeteries overflow and the dead are thrown “all over the place like ship cargo” into ditches?

“So many died that everyone believed it was the end of the world,” reports Agnolo di Tura from Siena, the chronicler of the Black Death, after burying his five children with his own hands. The plague as a divine punishment does not preclude the search for the culprits on earth. In the 14th century, fear and anger were directed against the Jews. A wave of pogroms swept over Central Europe, at the end of which there were hardly any Jewish communities left.

Today, conspiracy theories are still circulating in isolated cases during the coronavirus pandemic: Greek media report that Turkey is sending infected migrants across the border as biological weapons. The mutual accusations between China and the USA of being to blame for the pandemic and even of having deliberately triggered it, on the other hand, tend to fall into the realm of political propaganda.

But, taken as a whole, the scientifically-inspired interpretation prevails. It also produces its cult figures. For instance, the stoic Doctor Fauci, who tries to keep his employer in Washington on the ground. Apart from a few exceptions, the religious interpretation of an epidemic has become obsolete. Otherwise, how could an Anglican clergyman argue in favor of closing places of worship, claiming that the virus does not care whether he is in a gambling house or a church.

What for centuries was regarded as God’s punishment is today often interpreted in a similar line of thought as “nature’s revenge”: in the exploitation of nature (creation), man oversteps every boundary and is held accountable by the virus.

The epidemic calls for authority

Despite all the time-related differences, epidemic outbreaks always produce something similar. Containing the epidemic requires action by the authorities. The authorities issue regulations and create institutions to deal with the crisis. Some historians date the beginnings of a public health policy to the quarantines imposed in the years of the “Black Death” (1346-1353), which killed a third of Europe’s population.

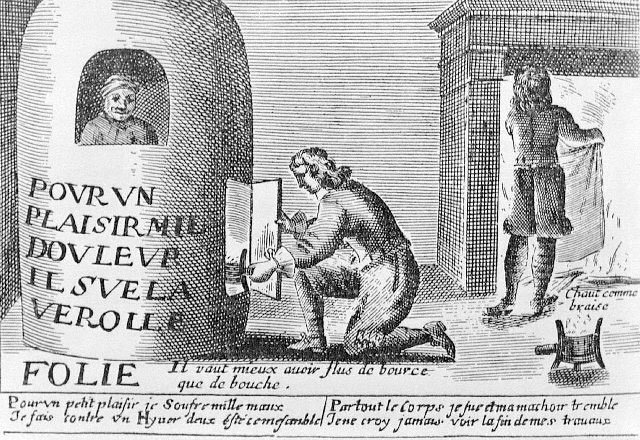

In the 15th century, Venetians established quarantine stations on their islands during a plague epidemic. Only after forty days were the crews of incoming ships granted access to the city. So quarantine existed long before people knew about the pathogens and their transmission routes.

The same applies to bans on leaving the city, the suspension of economic activities, the interruption of trade routes, and the sealing off of cities and regions. These measures were effective and became popular. To this day: as long as there is no vaccine against new viruses, modern societies will continue to rely on medieval defense measures.

Legitimized by the danger of the epidemic, the authorities established an order that regulated the mobility of citizens in the area. This is a topic of the French philosopher and historian Michel Foucault (1926-1984). He sketches three models of state power development, which he associates with three contagious diseases: leprosy, plague, and smallpox.

This is not a history of the pandemics, as Zurich historian Philipp Sarasin notes. Rather, he says, these models are about different ideal types of power. The large leprosariums at the gates of the city disappeared at the end of the Middle Ages.

Now, according to Foucault, the way in which the authorities dealt with the epidemics, which consisted of separating the sick from the healthy and leaving them to their own devices, also changed. With the modern age, a new practice began. The plague model: To ward off the epidemic, the movements of the subjects are strictly regulated and controlled. Areas are cordoned off, control posts are set up and citizens are confined to their homes.

Discipline and movement control

“The space solidifies into a network of impermeable cells. Everyone is bound to their place. Those who move risk their lives: contagion or punishment,” Foucault wrote.

However, Sarasin stresses that this “political dream” of the powerful, the far-reaching organization, and monitoring of plague-ridden cities, has hardly ever been achieved. Rather, he illustrates the ideal of power in the 17th century: the ruled city with disciplined citizens. A historical constant becomes visible: the epidemic is invariably the executive’s moment.

But the practice of exercising power is changing. In the 18th century, authorities adopted a different approach to the epidemic. The smallpox model was used to produce surveys that provided information on the mortality of both young and old, and the first vaccinations were administered, the success of which the authorities sought to determine.

The focus is no longer on disciplining or imprisoning the sick, but rather on risk management. The age of medical campaigns is dawning. The power of the state is thus growing, but it is not simply enforced by the police. Citizens must learn to coexist with the pathogens through official information and instructions.

Monitoring even in “normal conditions”?

During the coronavirus pandemic that we are now experiencing, European governments are more or less following the liberal smallpox model. The widespread information available makes the decision to be monitored understandable, and almost everyone complies with it. However, even in established democracies, governments are now ruled by the inherent logic of the social subsystems, economy, and science, subject to the primacy of the law: There is a state of emergency.

The aim of the measures, however, is to overcome the epidemic and return to a “normal state” with the familiar “checks and balances” and guaranteed freedoms. The state’s power of control is also growing in this epidemic. How many citizens were hitherto aware that authorities and telecommunications companies could always know where we were and with whom?

In addition, we are now being monitored through apps that are designed to protect us from infection and disease. They take away our fears but invade our privacy. Will health insurance companies in the future control the way we move around (enough and in the right place) – and then calculate their rates? Who controls the controllers?

The coronavirus crisis brings us a huge step closer to the police state. In the aftermath, we must rebalance the equation between freedom and security.