RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – For weeks, with China already paralyzed and supply chains striking the first blow, the word recession remained outside the common lexicon: the debate still revolved around how much the coronavirus would subtract from growth.

But the pandemic reached the West and doubts quickly became volatile: a confined economy leaves little room for escape. There will be recession in Spain. There will be recession in Europe. There will be recession in the United States. And there will be recession in Latin America.

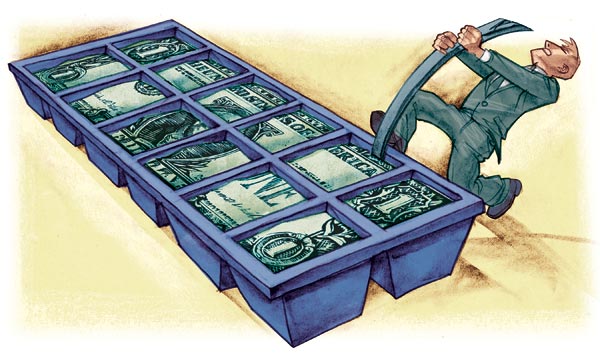

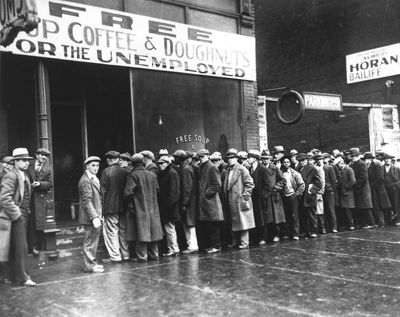

The initial ruin will be tremendous, almost certainly greater than the 2008 and 2009 recession, and the economic authorities’ current challenge – governments, central banks, IMF, World Bank, G20, G7 – is to prevent this time-limited blow from turning into something else: a Great Depression, as in the 1930s. Success depends, to a large extent, on experimental methods: freezing the productive sector until the nightmare is over, and then waiting for the activity to revert, as closely as possible, to where it was before.

In short, avoid a short circuit in the production system that strangles growth for years rather than months.

“It is already too late to avert recession: we are facing a massive and sudden slowdown, with devastating effects on both consumption and production. But we can and must do everything possible to prevent a depression. This is the challenge that will define an entire generation,” said Mohamed El-Erian, head of Allianz’s economic advisory and former president of the US Global Development Council under Barack Obama.

“We’re in what’s most like a dead period for the economy, where people and businesses need, above all, to survive,” says Alan Blinder, a former Fed number two and White House advisor in Bill Clinton’s presidency. As long as the stop lasts, all efforts by governments and central banks will be directed toward a single goal: to do everything possible to get them out of this predicament. “Support less privileged families, grant credit to businesses and prevent insolvencies and dismissals,” adds Ricardo Reis, economist at the London School of Economics (LSE).

The economy has entered a dark, self-inflicted tunnel, recalls Grégory Claeys, of the Bruegel think tank, with the greatest imaginable goal: to save lives. The US shifted in record time from full employment to a projected 20 percent unemployment and Goldman Sachs is expecting a double-digit contraction in Spain.

In uncharted waters and without a beacon from the past to light the way, this time, as economist Carmen Reinhart wrote, it is different.

And the treatment prescription should be different, too. In extraordinary circumstances such as these, it is now up to economic policy to play a very different role from the one it is used to: to try, by all means, to ensure that the productive base preserves its basic features without major interruptions, until business activity returns to the streets.

To subject the productive sector, in other words, to a kind of induced coma or deep freeze that keeps the vital signs as intact as possible, so that when everything passes, the way out of the crisis will be in the form of a V rather than an L.

Can an economy be frozen? “It is possible, yes, though very complex. And it depends on how long: if the total shutdown is extended, it will be catastrophic; if it is only a few weeks or months, we can avoid disaster… To do so, it’s necessary to prevent companies and jobs from disappearing,” says Reis.

There are virtually no historical precedents. Perhaps the Second World War, says the LSE professor without much certainty. Or, as Barke Eichengreen of Berkeley recalls, the one about the infamous Spanish flu: “But it was some cities, not a global freeze like this”.

As long as there is no consumption to encourage, says Sung Won Sohn, president of SS Economics and professor at Loyola Marymount University, the goal will remain something as simple to say and as difficult to achieve as avoiding a hecatomb in the form of an avalanche of bankruptcies and permanent layoffs.

And to ensure that the crippling wounds to the financial sector are as mild as possible: out of all the spotlights, the alarms have already gone off there, with the huge US mortgage market (12 times Spain’s GDP) experiencing its greatest turbulence since the 2008 crisis. “We are facing the first recession in history led by the service sector. If it lasts long and affects the solvency of banks, it could be even worse than the Great Depression”.

The casualty of labor and worse access to credit, for instance, greatly entangle the task of cryogenization in emerging countries.

Meanwhile, most European countries and the United States have already set to work, vetoing indefinite layoffs and gambling on temporary formulas in which the treasury covers a substantial part of salaries or dumping millions in liquidity for companies.

The events in March, however, have made some things clear. Public debt will hit the clouds and there will have to be cuts on the private sector, as Mario Draghi alerted this week in the Financial Times. “…part of the government loans [to businesses] will never be repaid,” Blinder said.

Later, when people return to work and consume, there will need to be more: “Consumption will need support, with a new round of incentives that, fortunately, developed economies can face due to such low interest rates,” Eichengreen said, no doubt arguing for the role of the state at times like these.

But the void has turned others into Keynesians: today no one denies its prime significance to prevent a total collapse. And they will need to do so afterwards too, by lending a hand in paying taxes and assuming their social responsibility.

Otherwise, concludes Ian Greer, from Cornell University, “once again governments will end up rescuing investors and passing on the costs to society through austerity measures”.

Exceptionality also leaves lessons learned. Central banks were much quicker to reflect this than in 2008.

“The role of states and central banks is encouraging, acting quickly and adopting emergency measures,” says El-Erian. The Fed and the ECB have been forceful: They’ve done their part. And the mistakes made, like Christine Lagarde’s in her first appearance – “we’re not here to reduce the spreads”- have been corrected “in two days and not in two years, as before,” Claeys notes.

Source: El Pais