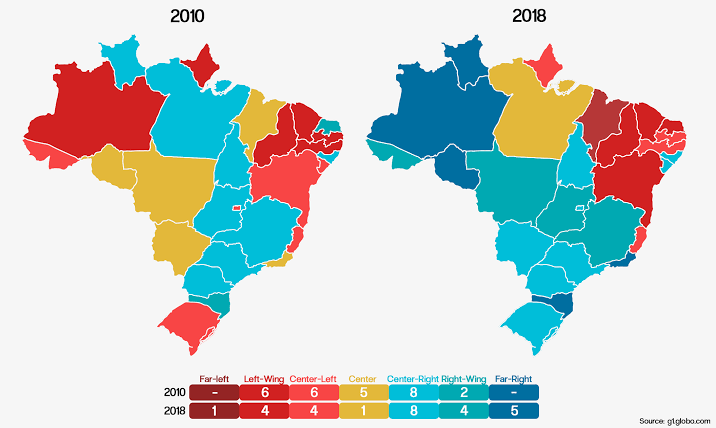

RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – Jair Bolsonaro is approaching his one-year term as President of the Republic. During this time, the virtual space that harbors Bolsonarism, and which was a key component of his campaign to come to power, has undergone some changes and has become divided.

The far-right-wing ideology is still there, intact and even more radical.

However, the unity achieved by Bolsonaro in the last elections has been broken. The extremists are now divided into at least three subgroups, explains David Nemer, an expert in computer anthropology.

In one of them, which he refers to as “insurgents”, are people with the same profile as the hooded men who claimed the Molotov cocktail attack on the headquarters of the producer ‘Porta dos Fundos’ in the early hours of December 24th. They relate to fundamentalism, the neo-fascist movement that emerged in the 1930s and which, in the internet era, gains new momentum.

“The insurgents are more militaristic and ended up becoming opposition, because they believe that Bolsonaro gave in to the establishment and is not radical enough. They believe that the only way to save the country is to carry out an armed insurgency to close Congress and the Federal Supreme Court, and start from scratch.

They speak extensively of armed insurgency,” explains Nemer, who since 2018 has been involved in WhatsApp groups on the far-right to monitor their behavior.

In a video that has been circulating on social media since last Wednesday and is now banned on YouTube, the hooded men who claimed the attack on the ‘Porta dos Fundos’ say they are part of the National Popular Insurgency Command, recalls Nemer. The Brazilian Integralist Front (FIB), on the other hand, released a statement denying any relationship with the men who took part in the attack.

Although it is not possible to say that those specific people are part of the WhatsApp groups that he monitors or that are officially linked to fundamentalists, the researcher explains that “the Christian nationalist tone and the ideas of attacking universities and institutions” are the same.

He also recalled that the same group that claims to have attacked the production company invaded UniRio in 2018 and burned anti-fascist flags, according to Ponte Jornalismo media outlet. These radicals work on darkweb forums, but also recruit new people through WhatsApp and YouTube.

“I couldn’t identify a single channel on YouTube because they are constantly banned or quarantined. So there’s a rotation,” adds the researcher.

The “propaganda hub” is yet another subgroup that Nemer spotted after the election. Made up of Bolsonarists who unconditionally support the president, it has become a kind of government watchdog, acting according to the daily political agenda.

In networks, these people stand up for Bolsonaro’s management in sensitive situations – for instance, at times when he challenges Congress – or when he finds himself in the throes of the international crisis unleashed by the fires in the Amazon.

“Bolsonaro needs an enemy to feed the rhetoric of them against us. And these people in the networks need an enemy to work with. In that sense, the Peronists have become enemies, Macron has become an enemy, and even people in the PSL have become enemies. They act like a virtual militia and even people like Alexandre Frota and Joice Hasselmann have become targets,” explains Nemer, mentioning the two deputies who broke up with Bolsonaro after being elected by campaigning for him.

Finally, the researcher further identified the subgroup he classifies as “social supremacists”, who are more closely linked to the evangelicals and can be as radical as the insurgents. “Social supremacists are not very attached to day-to-day politics, but they capitalize on the discourse of the president and his son, federal deputy Eduardo Bolsonaro. They share neo-Nazi, racist, anti-LGBT, anti-Northeastern content…” explains Nemer.

“After all, if the president’s son uses similar rhetoric and nothing happens to him, then these people, who are anonymous, feel greater freedom to share these contents. Bolsonaro’s government greatly validates this racist thinking they have”.

Why has Bolsonarism been divided into three subgroups?

The researcher points to the very nature of the last elections. “Bolsonaro embraces several lines of thinking: the liberal in the economy, the evangelical, the military… These lines are conflicting, they don’t go hand in hand, as we saw during the dispute between Olavo de Carvalho’s followers and the military,” he argues.

“These groups were all lined up in a message to elect Bolsonaro, but they began to clash. Some people wanted greater militarism, others wanted more Olavists, others more evangelicals. It is a reflection of what Bolsonaro is doing in real life: if he would fire a military official, then the militarists would be outraged…”, he continues.

So people were leaving WhatsApp groups set up during the campaign and building others more along the lines they wanted the president to follow.

Full professor and researcher in the Department of Media Studies in the University of Virginia, Nemer conducts his fieldwork in a virtual environment, to investigate how people behave and interact with each other.

Last year, he found that family group conversations were changing and taking on a more political tone as elections approached. Something apparently normal, but that gained momentum with the spread of home-made content – that is, unprofessional – with fake or distorted information.

He was also among those who identified the behavior of virtual militias that act to persecute selected public figures and destroy reputations. He himself became one of the targets of these virtual militias this December. When he published his reports, he claimed to have received e-mails with threats and even a photo of himself walking around a location in São Paulo.

With elections approaching in 2018, Nemer joined four WhatsApp Bolsonarist groups to monitor them. At the time, he identified a hierarchical way of acting.

At the top of the pyramid were a few anonymous people that he classified as influencers, responsible for generating misinformation and distributing it to these groups.

In the middle of the pyramid were what he calls a volunteer army, that is, Bolsonarists who were in charge of spreading this content to networks and family groups. At the base were the ordinary Brazilians, people who met Bolsonaro and promoted his candidacy.

“They were people who had no space for debate and were bombarded with content. Because of the recurrence, there was no room for doubt”.

With Bolsonaro’s election, many of these ordinary Brazilians left the groups, which ended up deflating. The most radical remained, dividing into the subgroups explained above.

Today, Nemer monitors some ten WhatsApp groups and has already collected reports of people claiming to have received amounts of money to boost fake content in networks.

“It’s a minority, something smaller than it was before, but it’s an extreme and radical minority. We need to pay attention because these dark, hidden spaces promote radicalization. People no longer have any critical sense,” he explains.

This minority today works from the politics of fear, trying to create a mythical past, which did not happen, to motivate people to go out and vote or protest, he explains.

“Misinformation doesn’t just want to drive a political agenda. It alienates you from the truth and takes away all your critical thinking,” he adds.

Source: El Pais