RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – The Amazon region is at the heart of attention due to devastating forest fires and the controversial environmental policies of Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro.

This natural wonder covers about 61 percent of Brazil’s national territory and is the world’s largest connected tropical forest. The region comprises 98 percent of indigenous land, 77 percent of nature reserves and the lands of Afro-Brazilian quilombolas. Together, these three conservation areas account for 32 percent of Brazil’s territory.

Its extent and biodiversity are home to 170 indigenous peoples, 357 permanent “quilombos” (rural settlements with predominantly black population, originally founded by escaped slaves), and thousands of communities of rubber harvestors, dried fruit collectors, riberinhos (inhabitants of the river banks), and babaçu coconut collectors settled by agrarian reform programs. The Amazon is home to many peoples, some of whom have lived there for more than 11,000 years.

The region, which holds approximately one-fifth of the world’s freshwater, stores substantial amounts of carbon in its rich forests and soils that would otherwise build up in the atmosphere and contribute to global warming. It is also a habitat for thousands of species of scientific and human interest.

The Amazon plays a vital role in the integration of South America. Among the five countries with the greatest biodiversity in the world are Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela. Bolivia, Guyana, Surinam, and France (French Guiana) are also part of this biome.

The fight against deforestation, the activities of loggers, illegal burning, the disorderly expansion of the livestock and soy industry, as well as the construction of large projects for mineral extraction, energy production, and road construction, which bring with them major consequences for the habitat, culture, and viability of the Amazonian population, is a necessary struggle in Latin America and for the peoples of the world.

Agribusiness in the Amazon

The green revolution of the 1970s transformed agricultural monoculture into an engine not only of food production but also of neo-extractivism applied to intensive agricultural use. The industry of agricultural chemicals developed; Brazil is one of the main users.

The result we see today is devastating, particularly in terms of soil contamination, watercourse contamination and human health consequences. This progression of monocultures in the production of cereals (soy, millet, wheat), oil crops (African palm), and eucalyptus plantations, implies intensive exploitation and extraction of resources, nutrients from the soil, water and groundwater.

Deforestation in the region has intensified with the construction of new roads and the disorderly construction of cities on their borders. In 1960, the Amazon region contributed as little as three percent to national timber production and in 1990 it was 27 percent.

Over the past 15 years, we have seen three lines of agribusiness capitalist growth. First, the use of technologies produced by transnational corporations that, based on transgenic seeds, have taken the green revolution to an extraordinary level.

Ideologically, the genetically modified plants are being sold as civilizational progress, as a modernization that would allegedly defeat Brazil’s agricultural problems and also reduce deforestation.

The second line is the progress of the agricultural sector itself. Although the governments under the Workers Party (PT) have fought deforestation in the Amazon region by developing systems that combine social, environmental and security policies and advanced monitoring, the agribusiness industry has insatiably invaded the Brazilian Cerrado, the world’s largest savanna and Brazil’s second-largest biome.

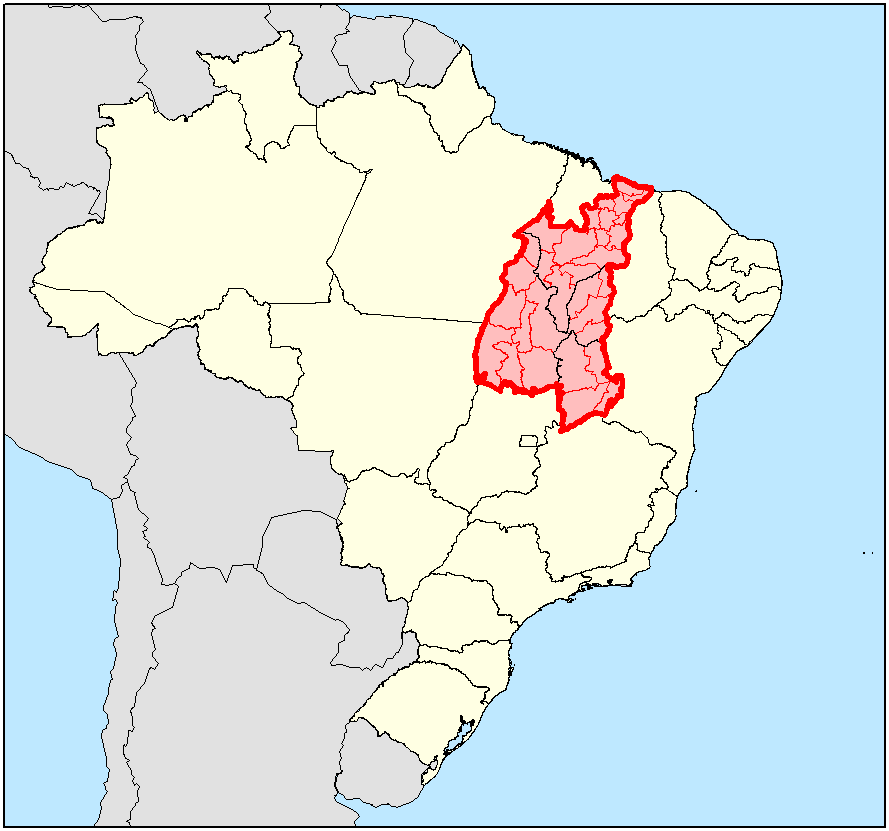

It is estimated that in the past ten years approximately 50,000 square kilometers of Cerrado have been deforested. The greatest symbol of this process is the construction of “Matopiba”, currently the largest agricultural region in the world, comprising 10 million hectares of Cerrado in the states of Maranhão, Tocantins, Piaui and Bahia, where some 800,000 rural worker families live and produce.

The Brazilian state implemented a number of measures that enabled the expansion of the Amazon agro-industry, mainly by building a border that includes the Amazon rainforest and the states of Maranhão, Pará, Tocantins, Mato Grosso, Amazonas, Rondônia and Acre.

Soy production, which began in the Midwest region, moved toward the Amazon rainforest through large investments and cutting-edge technology. In 2011, 9.5 million hectares were used for agriculture in the Amazon region, 68 percent of which for soy production.

The third and last line, the most sophisticated in its approach, is that of green capitalism, which seeks to subdue the captured territories as well as the resistance of indigenous peoples, quilombolas and farm workers, who seek to preserve nature through sustainable production methods.

The savanna, productive after clearing.

This subordination results from mechanisms such as carbon credits, REDD (reduction of emissions through deforestation and forest degradation) and the provision of environmental services. These processes are invariably linked to a logic of financialization of nature.

There is a high concentration of agriculture among transnational agribusiness corporations, which strengthens the dynamics of what we refer to as the first line. The ten largest companies in Brazil in terms of net sales are: JBS (Brazil), Raízen (UK/Netherlands/Brazil), COSAN (Brazil/Great Britain), Bunge (Netherlands), Cargil (USA), BRF (Brazil), Copersucar (Brazil), Marfrig (Brazil), Amaggi (Brazil) and Louis Dreyfus Company (Netherlands).

In this Amazon territory, the large transnational global corporations, which are seeking monopolies in the cereals sector, are operating through projects that promote logistics for the marketing of soybeans. Cargill, Bunge, ADM, among others, are the large export-oriented companies in the sector. This oligopoly with only a handful of companies turns the region into a large food importer because all soy and livestock production goes elsewhere.

Soy is the third most exported product in the northern region, after iron and copper. In the region with the largest soybean plantations, the state of Mato Grosso, 43 percent of all exports come from this commodity, followed by maize with 15.2 percent. In 2011, the multinational group Bunge concentrated 20.8 percent of exports in this state, followed by ADM, Louis Dreyfus, Cargill, Amaggi, Sadia and JBS.

Beef production in the area is progressing in the same way, increasing deforestation and land use. In 2016 there were more than 85 million cattle, representing more than three cattle head per inhabitant of the Brazilian Amazon. This growth has taken place with great support from the Brazilian state through public investment, where the JBS-Friboi is a model for the large Brazilian meat processing companies.

In Brazil, there are currently some 350 million hectares of farmland. The areas under cultivation cover 64 million hectares, livestock 159 million hectares, 50 million of which are already damaged pastures, i.e. highly unproductive.

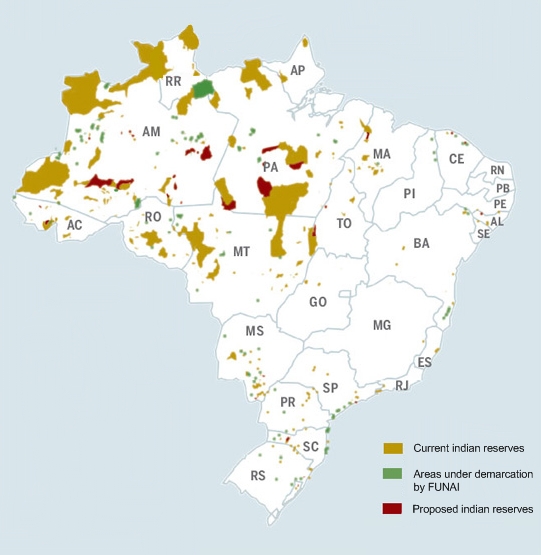

On the other hand, approximately 100 million hectares have been protected in nature reserves, 110 million hectares have been declared or are in the process of being declared as indigenous territories. It is therefore a continental-size dispute.

Social and agricultural conflicts, some pressing challenges

The denial of conflicts over land, workers’ rights and the preservation of culture and the organization of the inhabitants of the Amazon only reinforces these struggles and the desire to build another society that respects these territories and whose development must be reflected by its entities, while distributing land and preserving the environment.

As deforestation progressed with the removal of timber, serious conflicts broke out between the Amazonian peoples and the workers with the big landowners. In 1980, Wilson Pinheiro, the leader of a union of agricultural workers, was murdered. On December 22nd, 1988, another trade unionist was murdered: Chico Mendes, president of the National Confederation of Agricultural Workers of Xapuri.

A sequence of murders and massacres began and continues today. In 1996, the landless movement (Movimento dos Sem Terra, MST) witnessed the massacre of Eldorado dos Carajás; missionary Dorothy Stang, who organized workers’ resistance to the invasion of their territories by timber merchants, was executed in 2005; environmentalists José Claudio Silva and María do Espiritu Santo da Silva were murdered for denouncing deforestation and the seizure of land through tampered documents.

After a period in which the murders of political leaders of agricultural workers had slowly but surely decreased, the year 2016 showed a reverse trend. In 2003, the first year of Lula’s government, there were 73 murders. From then on until 2015 the murders continued in alarming numbers, between 25 and 39 leaders were murdered annually by the landowners’ armed personnel. In 2015, when the country was already in turmoil due to the preparations for the Coup, the number of people murdered rose to 50, 61 in 2016 and 70 in 2017.

Brazil’s Amazon is plagued by territorial conflicts and is in a dispute over development projects. The resistance comes from agricultural workers, indigenous peoples and quilombola communities who defend their constitutional rights to the land.

Popular movements continue their struggle for comprehensive agrarian reform. In urban areas, the housing movements continue, along with the LGBT, women’s, black and workers’ movements in the various companies that run major projects.

The 1988 Brazilian Constitution states (Article 231) that indigenous peoples have original rights to the lands they traditionally inhabit. In total, 13 percent of Brazilian territory is classified as indigenous; not coincidentally, it is the best-preserved part of the country, as barely two percent of deforestation is found in these areas. In some regions of Brazil, these areas exist only in isolated cases, islands of biodiversity.

These movements of resistance form a political force whose common denominator is rooted in the great themes of political ecology. In fact, there is an extreme increase in environmental conflicts in all regions of the Amazon in different countries. Because foreign agents led by a colonial perspective get there with money and power and cause the displacement of people, projects, cultures, and knowledge.

Aligned with the neoliberal ideal, the current federal government seeks to flexibilize and reduce the monitoring and controllability of environmental impacts. The government does not even acknowledge global warming; it ignores or contests science and environmental research, as well as the work of organized groups and experts on the environmental problems that are relentlessly caused daily in the country.

Recently, we have witnessed threats to withdraw Brazil from the Paris Agreement and liberalize the emission of greenhouse gases, further enhancing the prospect of freeing up forest lands for economic development.

The environmental disaster facilitated by Vale in Brumadinho, Minas Gerais, is one of the crimes that must be seen in the context both of the neo-extractivist model, which produces minerals on a large scale, and of the accumulation of waste at the point of production. The most valuable part of minerals is exported; what remains (tailings) is toxic, useless and dangerous. It is waste that accumulates in mountains and buries the dreams of many people beneath it: people, houses, villages, fields, rivers, and lakes.

The effects of development models, such as deforestation, loss of water quality and climate change, may be irreversible, or not; more and more, conscious people must be willing to make decisions about collective rights, a debate that involves us all.

The key is to understand the urgency of replacing this ancient model of plundering the earth, of predatory development, with another that safeguards the interests of the collectivity, of society and of nature that is about to be destroyed today.

Resistance is part of the processes of self-determination in the sense that it is directed towards an emancipatory and decolonizing model that combines ecology and politics; the transition to an ecological model of territorial development, mediated by tradition, culture and a balanced coexistence with the rainforest.

The perspective demanded by the peoples associated with the forest is the preservation and development of new territories that guarantee their sovereignty over land, water and forests; the orientation of agriculture towards the production of healthy food and the construction of a new energy project based on the sovereignty of workers and respect for nature.